90 Years On: How the 1936 Maritime Strike Still Shapes Torres Strait Self-Determination

Ninety years after Torres Strait Islander workers stood together and refused to accept racism as the price of survival, the legacy of the 1936 Maritime Strike continues to ripple through the region and beyond.

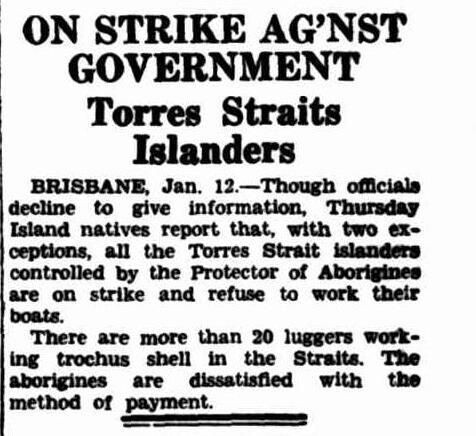

In January 1936, Torres Strait Islander men working in the pearling industry launched what is now recognised as the first organised Indigenous maritime workers’ strike in Australia. It was a bold collective stand against exploitative labour conditions, government control, and a system that denied Islanders autonomy over their work and their lives.

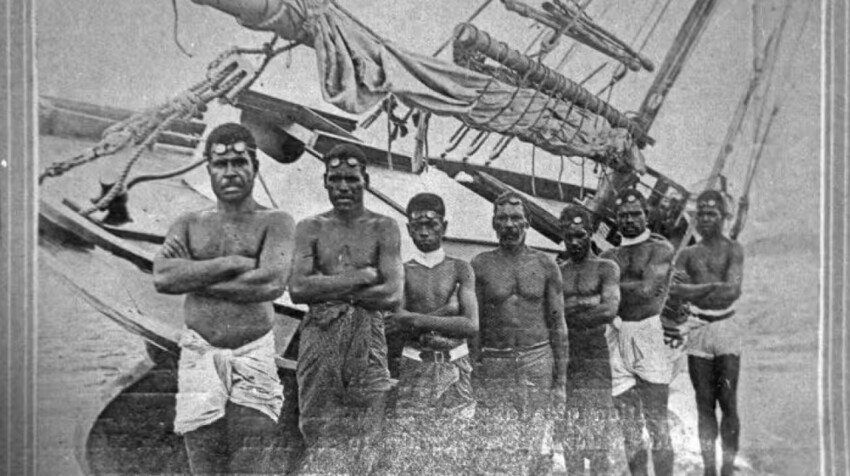

At the time, the pearling industry was the backbone of the Torres Strait economy. Since the 1860s, Torres Strait Islanders had worked dangerous waters alongside indentured labourers from Japan, Malaysia, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Timor, and across the Pacific. By the 1890s, the region was supplying half of the world’s pearl shell. Yet despite their skills and deep ancestral relationship with the sea, Islanders were subjected to strict control by the Queensland Government.

By the 1930s, that control was enforced through a local official known as the “Protector.” In 1936, that role was held by J.D. McLean, whose authority extended into almost every aspect of Islander life. Under his administration, Islanders were forced to work on so-called “company boats” which they built and crewed themselves but did not legally control. McLean decided who crewed each boat, managed personal finances, and could compel Islanders to work against their will.

Many workers were not paid wages at all. Instead, they were given store credit that could only be spent at government-approved shops. McLean also imposed a nightly curfew enforced by the infamous “Bu” whistle, further restricting freedom of movement.

For Torres Strait Islander workers, these policies were not just restrictive. They were deeply dehumanising.

The breaking point came in January 1936 when McLean travelled across the islands recruiting men for company boats. On islands including Murray and Badu, workers refused to comply. At a meeting on Badu Island, one man publicly explained why he would not sign on. He then led others in jumping out of the hall windows in protest, calling out that they would never sign back. The act became a powerful symbol of resistance and spread quickly across the islands.

Islanders made their position clear. They demanded wages paid in money, not credit. They rejected the curfew. They refused to work under a system that stripped them of dignity and control. Police responded with arrests, jailing at least 30 men who refused to work on government-selected boats.

Authorities attempted to weaken the strike by offering pay increases in February, but the workers held firm. As government officials later admitted, wages were only part of the issue. This was a broader fight for respect, equality, and self-determination.

Despite police presence and sustained pressure, the strike endured for months. Company boats remained idle. Islanders found support from the Anglican Church, South Sea Islander communities, Thursday Island traders, and even Japanese and European master pearlers who resented competing with a government-run labour system.

By mid-1936, the impact of the strike could no longer be ignored. J.D. McLean was removed from his post, news that was met with celebration across the Torres Strait. In September, his replacement Cornelius O’Leary introduced sweeping changes.

The curfew and Bu whistle were abolished. Wages were increased and paid in cash. Islanders regained control over crewing and operating their boats. Importantly, powers previously held by Protectors and government officials were transferred to Island Councils, returning authority to local communities.

By the end of the year, these reforms became known as the “new law.” The success of the strike laid the groundwork for separate Torres Strait legislation in 1939 and later inspired further collective action, including protests by Torres Strait Islander soldiers during World War II.

Today, the 1936 Maritime Strike is recognised as a turning point in the long struggle for Torres Strait Islander rights. As Gur A Baradharaw Kod Torres Strait Sea and Land Council chair Ned David has said, “Torres Strait Islander men stood together on the shores of our islands and said ‘enough’.”

While public attention has often focused on the 1937 Masig Conference, many now acknowledge that the spark for change was lit a year earlier, by workers who refused to be silenced.

As the Torres Strait marks 90 years since the strike, the story remains deeply relevant. It is a reminder that many of the rights Islanders exercise today were hard won through unity, courage, and collective action. It also speaks to broader struggles faced by Indigenous and Pacific communities, where control over land, labour, and culture continues to be contested.

The 1936 Maritime Strike was not just a moment in history. It was a declaration of dignity that continues to shape the present, and a legacy that future generations are still carrying forward.