State of the Nation Report Reveals Pacific Children Hit Hardest by Poverty, Unemployment and Benefit Sanctions

Nearly three in every ten Pacific children are living in material hardship.

Almost half experience food insecurity.

Pacific people now face the highest unemployment rate of any ethnic group.

And despite making up just 13 percent of welfare recipients, Pacific people account for 23.9 percent of benefit sanctions.

These are not projections or warnings. They are the current reality for Pacific children in Aotearoa, according to The Salvation Army’s State of the Nation 2026 report.

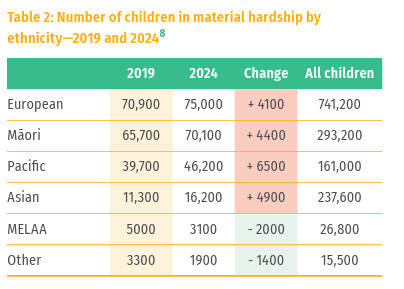

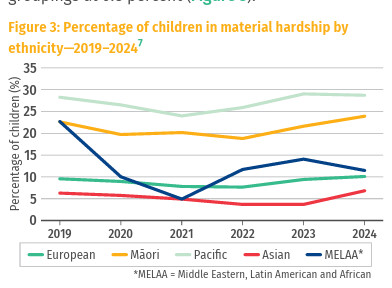

The report shows 28.7 percent of Pacific children are living in material hardship, the highest rate across all ethnic groups (p.7). That equates to 46,200 Pacific children, an increase of 6,500 since 2019 this increase is the highest amongst all ethnic groups in Aotearoa (p.8). While child poverty briefly declined nationally between 2018 and 2022, those gains have now been erased, with Pacific families falling furthest behind.

Material hardship means going without basics many families rely on: adequate food, warm clothing, heating, healthcare, transport, or stable housing. For Pacific children, hardship is no longer concentrated among a small group. It is widespread.

Labour’s Pacific caucus chair Jenny Salesa says the statistics reflect lived pain.

“My heart breaks for our Pacific children who continue to struggle. The statistics represent real stories, real pain being experienced by Pacific families who are being left behind by this government.”

Food insecurity and benefit reliance are rising together

Hardship for Pacific children is increasingly tied to hunger. The report shows 44 percent of Pacific children experience food insecurity (p.39), nearly double the national rate for households with children.

At the same time, the number of children living in benefit-dependent households is at its highest level in a decade. The report shows almost half of all children in material hardship live in benefit households, and 39 percent of children in those households experience material hardship, compared with around 8 percent of children in households supported by paid work (p.8).

Pacific people also experienced disproportionately more sanctions at 23.9 percent, while only 13 percent of welfare recipients are of Pacific ethnicities. Why is that?

Salesa says this points to a failure to protect children during a cost-of-living crisis.

“It’s unacceptable that almost half of Pacific children experience food insecurity and Pacific people have the highest unemployment rate of any ethnic group. Christopher Luxon promised to address the cost of living but instead, life has gotten harder.”

Unemployment surges in Pacific communities

One of the clearest drivers behind rising hardship is unemployment. Pacific unemployment has surged to 12.3 percent, the highest of any ethnic group and more than double what it was two years ago.

Labour Pacific peoples spokesperson Carmel Sepuloni says this is not accidental.

“Christopher Luxon keeps making life harder for our Pacific communities – and today’s unemployment data proves it.”

She points to the government’s decision to cut $22 million from Tupu Aotearoa, a programme that helped thousands of Pacific people into work.

“National cut $22 million from Tupu Aotearoa. Now, Pacific unemployment has more than doubled.”

Pacific workers are heavily represented in construction, manufacturing and service industries, sectors that have seen job losses, stalled projects and reduced investment over the past year. Sepuloni says the fallout is pushing families to breaking point.

“The construction sector, which is where many Pacific people work, has been gutted by this government. And now Pacific people are being forced to look overseas for work that should be available here.”

Rising harm follows economic stress

As financial pressure mounts, other indicators of child wellbeing are worsening. Reports of concern for child abuse or neglect rose 44 percent in 2025, the largest annual increase recorded (p.10). Substantiated cases of neglect increased 21.5 percent, while emotional abuse rose 11.3 percent (p.10).

In the same year, more than 9,000 children under the age of 15 were victims of violent crime, nearly 2,400 more than five years earlier (p.11).

The report links these trends to sustained economic stress following the pandemic, overcrowded housing, and reduced access to support services, conditions Pacific families are more likely to face.

Government says recovery is here

Despite the data, Prime Minister Christopher Luxon maintains the country is on the right track. In his State of the Nation speech in January, Luxon said his government would continue to run a tight budget and would make no “extravagant” election promises.

“New Zealand simply has to get its finances in order if it is to achieve a long-term improvement in its economic prospects.”

Luxon acknowledged rising unemployment and a surplus now delayed until 2029–30, but pointed to falling inflation, lower interest rates and increased business confidence as signs the recovery had arrived.

“I feel more confident than ever that the recovery has now arrived and Kiwis can look forward to a year which is brighter than the last few.”

He rejected calls for increased spending to ease hardship.

“Any party that wants to ramp up spending is being economically irresponsible.”

A widening gap between policy and lived reality

For Pacific families, the recovery described by the government is yet to materialise. Pacific children have experienced one of the largest drops in early childhood education participation since 2019 (pp.14–15), and disabled children and caregivers face even higher hardship rates (p.7).

Using Te Ora o Te Whānau, a Māori wellbeing framework, State of the Nation 2026 concludes that these outcomes are driven by systems, not individual behaviour: low wages, insecure work, rising housing costs, and welfare settings that fail to meet basic needs.

As political parties move deeper into election year, Salesa says the stakes could not be higher.

“While government parties squabble over each other, our kids are hurting. We need to take real action to get this right for our Pacific communities.”

For Pacific children, the data is already clear.

The question now is whether policy will catch up with reality.