Will the injection into Disabilities Learning Support Budget make a dent in the damage done?

“Our children are falling through the cracks”: Māori and Pacific families left behind in broken disability support system

When Montoya’s son was first labelled “naughty” at school, she knew it wasn’t his behaviour that was the issue — it was the system.

“He was struggling. He was overwhelmed. And stimming was his way of coping,” she says. “But too many people, including educators, simply don’t understand what it means to be autistic, because they’ve never been taught.”

Like many Māori and Pacific whānau, Montoya has had to become the system — the speech therapist, the advocate, the support worker — while trying to hold her family together. Her son has been on the speech therapy waitlist for six years.

“One speech therapist for 30 schools is not good enough,” she says. “Families shouldn’t be forced to fill these gaps on their own when they are crying out for help.”

Her experience is not isolated. Aotearoa Educators’ Collective’s latest report, Beyond Capacity: Learning Support in Crisis, paints a dire picture: an underfunded and overburdened system where tamariki with disabilities and neurodivergence — especially Māori and Pacific children — are consistently denied access to the support they need.

The report warns that some schools are now so stretched, they fear a student could die in their care due to a lack of resources and supervision. One principal told researchers their student faints up to 22 times a day — yet doesn’t qualify for high health needs support.

Even before the Budget, the government had already introduced cuts to disability care by narrowing eligibility criteria for support funding — a move critics say strips away choice and flexibility for disabled people and their families. Labour labelled the sudden changes "callous", accusing the government of breaking its promise not to touch frontline services.

While the Education Minister had promised a “learning support Budget,” principals said they’d heard it all before.

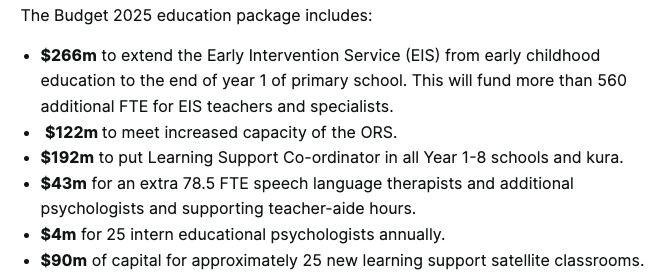

Now, Budget 2025 has finally arrived — and with it, a $2.5 billion injection into education. A significant portion of this will go toward students with complex learning needs. The government says it’s the “biggest boost in a generation,” pledging hundreds of millions to reform the Ongoing Resourcing Scheme (ORS), roll out more Learning Support Co-ordinators, and fund specialists like speech language therapists and educational psychologists.

Education Minister Erica Stanford said teachers have been crying out for help: “We don’t have the teacher aide support, the specialist support, the speech language therapists, the educational psychologists that they need. We are now making sure those supports will be available.”

Around $266 million will extend early intervention services through Year 1 of primary school, $122 million will meet growing ORS demand, and $192 million will place Learning Support Co-ordinators in all Year 1–8 schools. A further $90 million is earmarked for 25 new learning support satellite classrooms.

It’s a step forward — but is it enough to repair decades of neglect?

Berhampore School principal Mark Potter, a long-time advocate for children with disabilities, says schools have been waiting for something real and lasting. “What we really need is some serious, genuine long-term investment like the military just got. But we’ve been waiting longer.”

A funding system that wasn’t designed for us

Only 6–7% of students in Aotearoa receive publicly funded learning support, despite neurodivergent learners making up an estimated 15–20% of the population. The report confirms what many Māori and Pacific families already know — that those most in need are the ones being hit the hardest.

Janine Hall, a South Auckland mum, has felt this first-hand: “We’ve had to go through so many loops, waitlists, referrals and rejections, only to end up with nothing. We’re forced to constantly beg for help, and it’s still not enough.” She says her son’s school tried their best, but the system made it nearly impossible. “I had to give up work to be available full-time for my son, because the school just didn’t have the staff or training to support him. He’s not the problem — the system is.”

“It shouldn’t be this hard”

Montoya says inclusion shouldn't be something families have to fight for.

“Inclusion should be the foundation of our education system. But right now, the environment in mainstream schooling is simply not good enough,” she says. “There are so many children falling through the cracks — especially our Polynesian and Māori people — because the resources just aren’t there.”

Montoya is still waiting on wraparound support and has had to modify YouTube videos and speech therapy guides herself just to give her son a chance at communication.

“This is not how it should be. I’ve spent countless hours advocating, pushing, emailing. And I’ll keep doing it. Not just for my own child, but for all our children.”

Decades of neglect

Whether the Budget 2025 announcements will change the everyday reality for these families remains to be seen. The numbers are promising — but so were the promises in the past.

Montoya agrees. “We need more funding, more trained professionals, more awareness and, most importantly, a real commitment to inclusive education. Our children deserve better.” The money is finally on the table. Now the question is whether it will be spent in a way that truly reaches the children who’ve been left waiting the longest.

-

By Tikilounge Productions & Creative New Zealand Toi Aotearoa

Arts & Culture Journalist Destiny Momoiseā